Table of Contents

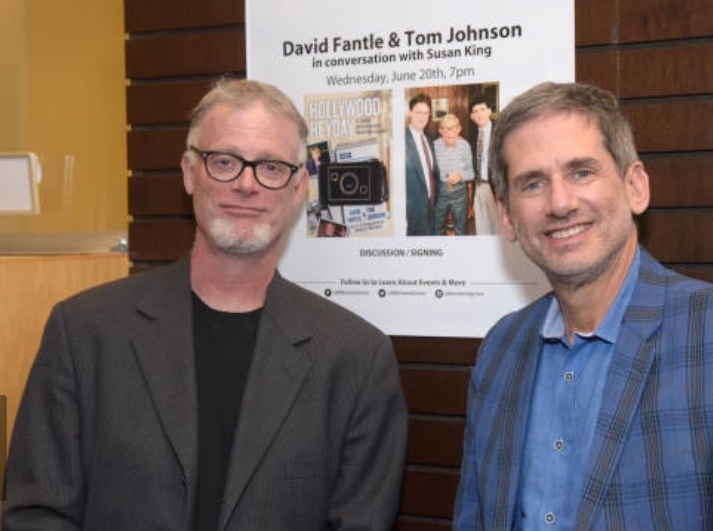

ToggleJanet Leigh & Tony Curtis: A Star-Crossed Couple

Once upon a time in Hollywood (the early 1950s to be exact), there lived a beautiful princess named Janet Leigh and her crown prince, Tony Curtis. As a married couple, their union in 1951 had been properly sanctified by an ordained minister and by God. Beyond that, it earned the beneficence of another — perhaps higher power — Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios.

You see, the star-crossed couple generated considerable box office heat in those days, with the hegemony of television making Pepto-Bismol the aperitif of choice for most movie executives, the king of studios responded ravenously to balance sheets in the black. And Leigh and Curtis with charisma galore certainly delivered the requisite numbers along with a large and soothing dose of old-style Tinseltown brio.

Generally, life was simpler back then — or perhaps just simply repressed. In any case, even media-generated “hype” and “spin” had an innocent hue and took longer to build than the egg-timer industry average of today. However, in the case of Leigh and Curtis, as the rpm of their individual careers increased, their combined “celebrity” became a veritable juggernaut drawing unruly crowds that literally buckled seaside piers during personal appearance tours. (Kim and Kanye, eat your heart out!)

Crowd Control

According to Leigh, the big difference between her and, say, today’s crop of young media-concocted icons (we talked to her in 1996) is that she was schooled by the studio to court publicity and, if not the adulation that sometimes came with it, at least learn how to take it in stride. Howard Strickling, head of publicity at MGM, taught her a valuable lesson in the 1950s, one she said that held her in good stead; it was the fine art of crowd control.

“The surge comes because the crowd thinks you are going to run away from them,” she explained. “So if you remain calm, they settle down because they think you’re extending yourself. It really works, but you’ve got to keep moving — never stop. If you stop, they’ll corner you.”

Leigh’s explanation wasn’t disdainful — far from it – it was a thoughtful, if somewhat dispassionate, deconstruction of crowd dynamics. For us, it conjured certain advice Midwestern farmers used to dole out when working around livestock. “… Move slowly, deliberately, no jerky movements and always keep a watchful eye on the bull.”

Cattle calls, we surmised, must be the same all over, be they of the four-hoof or two-legged variety.

We interviewed Leigh and Curtis – separate visits two years apart – at their houses, each perched on the spine of the Santa Monica Mountains but at opposite ends of that low, crusty range of hills.

Interviewing Janet Leigh

Leigh greeted us in the early spring of 1996 at the 10-foot-high driveway gate of her home just off Summitridge Drive in Beverly Hills, the same street that Big Band leader Artie Shaw had lived on in the early 1940s and for which he named one of his catchiest swing tunes. The gate effectively screened the house from any “Peeping Toms” who ventured into those oxygen-thin reaches of upper Beverly Hills to gawk at the immortal star of “Psycho.” Our first glimpse of her was when she gave the most furtive of peeks around the partition which she had opened just a sliver in order to ascertain we were who we claimed to be.

For just an instant, it felt to us like a distaff real-life role reversal of when Anthony Perkins as Norman Bates played the creepy voyeur looking through a peephole into Leigh’s motel room in that film.

“I’ve been stalked,” Leigh said matter-of-factly. “Jamie (her daughter with Tony, Jamie Lee Curtis) has had several stalkers, so she’s nervous. You just have to take precautions.”

All in all, the apple doesn’t fall very far from the tree in the Leigh household. Jamie Lee Curtis, started in the movie business starring in horror films such as “Halloween,” “Terror Train,” “Prom Night,” and “Friday the 13th.” To a generation of spooked teenagers, she earned the endearing appellation, “The Scream Queen.” Back in ‘96 Leigh was playing a part made to order in the latest in the latest installment of her daughter’s “Halloween” franchise – “Halloween H20: 20 Years Later” as, what else, Jamie Lee’s mom!

Separately or in tandem, with Janet Leigh and Jamie Lee, blood — along with a little bloodletting — does tell!

The house itself which Leigh shared with her husband, Los Angeles businessman, Bob Brandt, seemed like a continuation of the steep mountainside incline on which it was built – all angular rooms and vaulted ceiling; Westside modern meets Babylonian ziggurat.

“Here is where I draw the line between my public persona and my private life,” she said.

Looking svelte from a regimen of regular tennis matches with friends like fellow MGM star, Jane Powell, Leigh, 71, plopped on a sofa and told us that contrary to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s famous prescient pronouncement about his own trajectory, some American lives do have second acts.

“I’ve become a writer during these last several years,” she announced proudly. To that date, Leigh had written an autobiography entitled, “There Really Was a Hollywood,” as well as a well-received book on the making of “Psycho” which was published in 1995 to coincide with the 35th anniversary of the film. That same year she also published her first novel, “House of Destiny.”

“The first time I saw my name printed on the dust jacket of my first book, it was every bit as thrilling as seeing my face up on a movie screen for the first time in 1947 in ‘The Romance of Rosy Ridge,’” she said. “As an actress, you are such a small part of the overall movie, just a cog in the machine. But writing a book is introspective, personal and you go at it 100 percent alone.”

Psycho

According to Leigh, writing and performing were definitely aligned. “You prepare for a role the way you prepare a character for the written page,” she said. “For example, when I played ‘Marion Crane’ in ‘Psycho,’ I constructed her whole life. I knew what she was like in school; her tastes, frailties, strengths. I knew what kind of sister she was, and what kind of daughter.”

Just as Leigh faced a blank sheet of paper alone, she also flew solo developing her character in Hitchcock’s most disturbing suspense thriller. “Hitch had a hands-off policy unless you really were blocked,” Leigh said. “He was the consummate shot-maker and he trusted his actors to come up with their own motivations. I do remember that he didn’t feel there was enough passion between John Gavin and I in the opening hotel room scene, even with me just dressed in a slip and brassiere, so he told us to turn up the heat, which we did.”

It’s no shocker that Leigh remained unimpressed with the quartet of “Psycho” clones that had been lensed in the intervening years — although she saw them all. When pressed to choose the least objectionable entry in the series, she picked the 1990 made-for-cable prequel version. “In that one you saw what a loon Norman’s mother was, so you figured out why he went bats,” she laughed. Leigh added she had no intention of appearing in the big screen (unsuccessful) remake of the film that was subsequently made with Vince Vaughn and Anne Heche, a pallid substitute for Leigh as “Marion Crane.”

“The thing about Hitch, and this has been well-documented,” Leigh said, “was that everything was storyboarded, everything was down. He knew exactly where the actors were to stand in a scene, what lens was on the camera for a particular shot – everything. As an actor, what you have to do is bring what you want to bring to your character, but you had to move when he wanted you to move. That’s where the crossed swords came with many actors, because they felt that he was curtailing their creativity or their freedom of expression. You could take it that way.”

Leigh took it another way entirely, as creative latitude. “I took it in a way which I felt was healthier, since that was the way it was going to be, regardless.” she said. “I took Hitch’s direction like he was saying: ‘Look, you’re an actress. I’ve hired you. I believe you can do Marion and you can do with her pretty well what you want. Bring to her what you kind of have in your mind unless it interferes with what my whole concept is. If it doesn’t, I’m not going to bother you at all.’ I took his confidence in me as a supreme compliment.”

Leigh said that she was the only actor in the movie that was sent the novel “Psycho” by Robert Bloch with a letter from Hitchcock asking her to consider playing the role of Marion Crane. “I would have done the movie without even reading the book because of Hitchcock,” she said. “I mean, I would’ve been the biggest dumbass of all time if I said no.”

With her second career as a memoirist burgeoning, Leigh found herself in a nostalgic mood about Old Hollywood and what it was like when she started in the business.

“Oh, God, it was fantastic,” she said. “I was a part of something that I’d watched since I was born. I used to go to the movies all the time. To be a part of that; but then I really wanted to learn what it was all about. It was an opportunity. It was like going to college. I loved it.”

She also remembered her first day of work as a contract player at MGM as if it had happened the day before. “I walked in that gate twice,” she said. “The first time was when my agent took me from MCA and I walked through the pedestrian entrance of the big MGM gates and Jose Iturbi opened the door for me and I just about died. I mean, I’d just seen him in ‘Holiday in Mexico.’

“Then the next time was when I went back. I signed a contract that day,” she continued. “I got the appointment with Lillian Burns (the head dramatic coach at the studio) that day. I went back to MCA, signed all the papers, which I loved doing. Then the next time I walked through there, I walked through as a part of it. I walked through that gate that I had seen in pictures since I was able to go to movies, and I was a part of it. I belonged there. My name was there. The guard said, ‘Oh, yes … you’re on the payroll.’ I was a part of this fantastic organization.”

Interviewing Tony Curtis

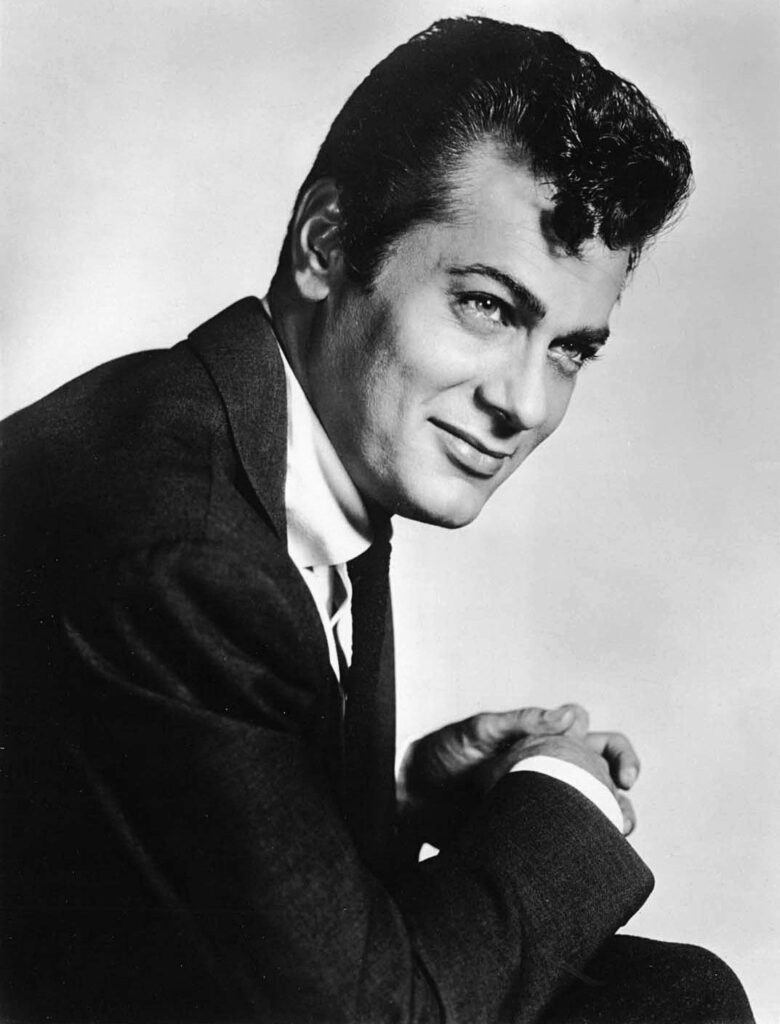

Two years later during our visit with Tony Curtis, he wryly admitted that he broke into movies the same way a thief enters the second story window of a mansion he’s going to rob — surreptitiously, almost undetected. It was the antithesis of Leigh’s dreamlike contract signing full of magic and stardust.

“People didn’t know who I was — I just snuck in,” Curtis said, laughing the same incredulous laugh he did in 1948 when Universal first put him, a largely unknown acting quantity, under the standard studio contract. “I was like a weed that grew out of a crack in the cement only that crack happened to be located on a studio lot.”

Thanks to an irresistible combination of darkly Semitic matinee-idol looks and an engaging grin that illuminated the screen, Curtis’s stealthy break-in to the business soon became a four-alarm fire. Separately, and with his equally photogenic wife, Leigh, Curtis became a monolithic sex symbol long before hype and marketing spin made such phenomena easier to construct.

“Janet and I ended up being a movie couple, but without intending to be,” he said. Curtis met Leigh at a cocktail party, but the studio balked when they became a regular item. “They didn’t like the idea that maybe I would even marry her. And that got me so pissed off that I did,” he said. “It gives you an idea how clumsy the times were. We fell in love and the next thing we knew all the magazines went ‘ga-ga’ over it. Eddie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds could have been our maids in comparison … Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton could have been the couple who lived in our gatehouse and looked after the garden. That’s how big the buzz around us was in those days.”

Hitting It Big In Hollywood

To hear Curtis retell it, his impact in films was unprecedented. “When I hit, in 1948, I really hit big,” he said, “and no one knows why. The movie guys up to that point had been in the service. The men were coming out and they were 35 and 40 years of age. There were no young leading men. It was Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas — who started after the war – but they were in their 30s already. But the young teenagers didn’t have an idol out of that maelstrom. It was Robert Wagner, me and Marlon Brando who came out about the same time. John Derek was at Columbia and Marshall Thompson was over at MGM. There was a half-dozen. But nobody punched it out like I did. I didn’t have to kiss anybody, kiss anything.”

Half a century later, the march of time – not the ravages of it – had tempered Curtis’s good looks into a formidable, but not vestigial presence. The rippling chest of yore, barrel-shaped in ‘98, still emanated powerful strength. And he still could high-beam that Pepsodent smile at will, which he did unstintingly. In fact, for Curtis, it had all become about living life in the affirmative.

Then 73, Curtis lived in a gated community in the hills of Bel-Air about a Henry Moore stone head’s throw across the 405 freeway from the Getty Center art museum. It was a propitious location for Curtis since acting in movies had largely, though not completely, given way to his second career as a painter. He told us that at last count he had perhaps 1,500 canvases and 2,000 drawings stacked in a studio he kept in Woodland Hills and which one of his sons managed. Looking around the living room of his hacienda-style house, much of the overflow seemed to recline against all available upright surfaces. Matisse-like still lifes were propped next to framed animation cells of Tony as “Stony Curtis” from “The Flintstones,” cartoon show, and blow-up photos of he and Jack Lemmon dressed in drag and reclining on a divan on the set of “Some Like It Hot.”

But apart from the multicolored neck ribbon of Curtis’s Légion d’Honneur (bestowed by the French Government for meritorious cultural achievement) which peeked at us from its half-opened box, very little chronicling Curtis’s show business career was visible.

“You wouldn’t know to look around here that this is the home of a movie actor. You’d think a painter lives here, and that’s the way I like it,” he said in that familiar low-clipped tone that conjured images of a street urchin boyhood in New York City.

Back to that medal. An impression many people had of Curtis the preceding last few years, largely through his appearances in the media, was of a loose cannon. Flouncing into gallery and nightclub openings with the Légion d’Honneur hung prominently around his neck like the “flair” on a Denny’s waitress smock, Curtis brought to mind a younger version of Georgie Jessel in all his overblown military regalia. It would’ve been easy to dismiss Curtis’s eccentricity, like it was Jessel’s, as a joke, a publicity ploy. But that would be wrong. Curtis, you see, made it abundantly clear that he didn’t give a shit! To wit; he had seen and done almost everything, and, good or bad, he had come out alive on this end wiser for the wear. To Curtis’s way of thinking, that clarity also provided the liberating freedom of not having to buckle to peer pressure — or pretty much any pressure. Curtis had, in effect, achieved a Zen-like state of placidity the last few years.

Better Than Ever

“My dear friends, every minute of the day it can’t get better than it is right now,” he recited, mantra-like, in the ritualistic cadence of a twelve-step program brochure (Curtis told us he was a program adherent after liberally abusing cocaine and heroin in the 1970s). “And that minute will give way to the next ‘best’ minute. I’m not jerking myself off here. I’ve never been busier. I’ve never looked better in my life. Everywhere I go people love me. I get tables anywhere in the world. And I love it all!”

An ego successfully rehabilitated? Almost. Curtis did confess to a kind of wistful ennui about receiving recognition from his Hollywood peers for what he considered to be about 20-25 great films out of 110 movies in which he starred. “That’s part of the uniqueness of my situation,” he said. “I’ve done some excellent films, like my favorite, ‘The Boston Strangler,’ but I guess I’ll have to leave any affirmation in the hands of the Gods.”

But really, affirmation of sorts came almost daily for Curtis. There used to be a mural of him in a white T-shirt (taken from an early Curtis role in “City Across the River” in 1949), painted by a graffitti artist on an overpass that spanned the Hollywood Freeway, and it could almost stop traffic. More famously, Curtis was depicted on the cover of The Beatles’ Sgt. Peppers album and, of course, there’s “Stony Curtis.” Not bad for the former Bernie Schwartz from ‘Da Bronx.’

However, in the end, Curtis exhibited a repeated penchant for green-glassing any lingering sentiment about his career. “My dear friends, I don’t give a shit,” he said. “It’s not that important, it never was and it never will be; it’s a profession, a career that I chose. And during the period of time when movies were made before television, that was when a lot of my movies were made, there was no such thing as, ‘Well, next year it’ll end up on a network or a program on TCM.’”

“Those tiny little pop-culture affirmations prove that I made my mark during a period of time,” he says. “They make me feel good but that’s all.”

Some Like It Hot

What didn’t make Curtis feel good when he was at his apex was working with Marilyn Monroe during “Some Like It Hot,” one of the very best comedies ever filmed. “She made it tough for everybody,” Curtis said. “If you’re in a chain gang and you’re tied to someone else, who’s also tied to someone else, and so on … and the fifth guy down the line is screwing around and not paying attention, it will delay everyone else. That was the case with Marilyn. You’re being paid good dough to work and you’re doing 10-12 hour days. You don’t want to have to baby someone unless the script calls for babying.

“She would play Jack Lemmon off against me or me against him and Billy Wilder against both of us,” Curtis continued. “We had to slow down for Marilyn because she couldn’t memorize lines at that time. She was quite awkward in her behavior with everybody. Marilyn was getting even with every guy who ever fucked her – anybody – any man that made her put those kneepads on! That’s my read on her. But I never said kissing her was like kissing Hitler! I don’t know where that came from.”

A full frontal barrage with Curtis telling it like it was — with no particular axe to grind or anything to purge. He told us he began to tell the unabridged truth years ago. “There’s nothing for me to be upset about,” he said. “There isn’t anyone alive who wouldn’t want to be a major player in Hollywood. Walk down the street and point to anybody. You get everything you ever wanted.”

Through the years, various actor friends and artists shared with Curtis pearls of wisdom that he filed away and learned from. One was from his acting idol, Cary Grant. “Cary once told me the way to judge a fine bottle of white wine was that after chilling, it should taste like a cool glass of water,” Curtis remembered. ‘It’s so artful that it’s artless,’ Cary said. Curtis instantly related Grant’s sommelier advice to his own profession and considered it one of the best acting tips he ever received; that less is more. Indeed, underplaying scenes may have helped ensure the long run Curtis enjoyed in movies.

“I don’t want my work ever to look as if, when you see me in a scene and the subtitle comes underneath: ‘Watch Tony get mad now!’ You could do that with a lot of actors,” he said. “I know a lot of actors that telegraph what’s coming; Jack Lemmon does, George C. Scott does. I could name a whole slew of actors who are constantly telegraphing what they’re about to do, but that’s their style of working in a movie. There’s no one style to movies. Movies isn’t a profession like brain surgery where you’ve got to make certain cuts a certain way. Some people star in movies because of their tits; some because of their hair; some because of their size or their sex. One thousand years from now the films I made will probably still be around in some form,” he said. “If you look at it that way, they have their own kind of perpetuity.”

During the interview, Curtis had been intermittently doodling with a pencil on a small sketchpad. As he got out of his chair, he handed us the sketch he had been working on of a hand pulling a cord dangling from a floating cloud that was rendered in the shape of a smile.

It was Curtis depicting for us the equilibrium he had come to feel – that life was good; weightless, in fact. And who could ask for better affirmation than that.