The Manopause Team is presenting this thoughtful article about the AIDS pandemic, which was written by Alex Langford several months before the COVID era. We felt it has become even more timely and resonant since then. With COVID, if a youngster brings the virus home to parents or grandparents, the consequences can be devastating, and the subsequent guilt overwhelming if their loved one dies. Another side to the “Survivor’s Guilt” occurs if one spouse or sibling or friend dies from the virus even though both were infected. The inevitable thought is “Why did I live and they died?” It’s a problem that society will be dealing with for some time. And there is no answer. Only support.

It was New Year’s Eve, 1995. Rapper Easy-E, major league ball player Glenn Burke, and poet Essex Hemphill had all died of complications from AIDS in the past few months. A shadow of death was all around the Bay Area. Still, life went on – at least for some of us in San Francisco. A few friends had gathered in an apartment to wrest whatever happiness we could from an end of the year celebration.

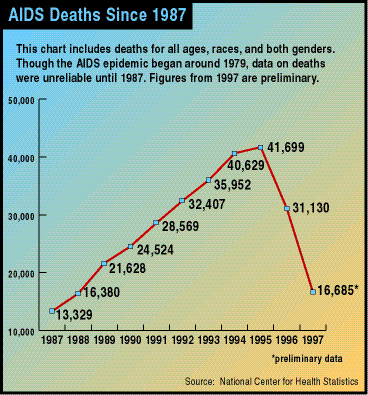

We later discovered that 1995 was the peak for AIDS-related deaths in the U.S. It claimed over 41,000 Americans that year.

I was a journalist in San Francisco at the time, and AIDS was fairly new. I became accustomed to losing people on a regular basis. My friend, filmmaker Marlon Riggs, had died the year before. He fought valiantly. I remember rubbing his feet as he lay in his hospital bed. It helped him relax. Singer Sylvester, who I once spent two days interviewing, was an even earlier victim. He died in ’88, a time when the disease barely had a name.

Some of us who managed to live – the Baby Boomers who reached their thirties in the ’70s and ’80s, now call ourselves survivors. But with that survival also comes what psychologists call Survivor’s Remorse, or Survivor’s Guilt. It is defined as “a significant symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It may be found among survivors of epidemics (like HIV), as well as survivors of combat, murder, natural disasters, rape, and terrorism, and it is found among the friends and family of those who have died (American Psychiatric Assn, DSM-5, 2013).” It may sound dramatic to say people who were lucky enough to avoid HIV as it raged through our communities suffered PTSD. But it was a dramatic time, when a simple sexual act could mean life or death.

Why did the virus strike some of us and not others? It’s important to realize how mysterious the epidemic was in its early days, even in regards to its name. The term AIDS was first used by researchers in 1982. “Gay cancer” and “gay plague” were common names in ’82-’85. For a very short time, G.R.I.D. was used, standing for Gay Related Immune Deficiency.

It was in this climate – of ignorance, tragedy, ridicule and fear – that we lived. At about this time we were told HIV was spread by bodily fluids, and that safe sex was the best protection. That information came too late for some. And still others preferred not to use condoms. In the adventurous post-disco days of the ’80s, it was often impossible to know, all things being equal, exactly how you got the virus – if you did – and how you avoided it, if that was the case.

So friends, family and famous people continued to fall. Entertainers Jermaine Stewart, Fela Kuti, Howard Rollins, and my friend Sam Sanders were claimed by the virus in ’96-’97. So many people died that San Francisco’s Black population fell from a historic high percentage of 9.0% in 1980 to 6.4% in 2010 (Haas Institute, UC Berkeley, 2019).

This had a devastating effect on social networks. Friends and acquaintances were falling on a weekly basis. At the same time, Black men were also at risk from the threats of mass incarceration and the crack epidemic. The epidemic, the tough-on-crime trend, and AIDS together created a three-headed hydra that claimed the lives of thousands of young men and women who were just starting their adult lives.

And yet, some of us survived and carried on, avoiding the “hydra.” We’ve had children, relationships, success and disappointment. Survivor’s remorse encompasses “the psychological effects of living with the long-term trajectory of the AIDS epidemic and includes survivor’s guilt, depression, and feelings of being forgotten in contemporary discussions concerning HIV.” Nothing in life can prepare you for living in a vibrant creative community of friends one minute, then quickly seeing those friends disappear, especially at a young age and unexpectedly.

So what lessons have survivors learned, and what wisdom can be passed on to younger generations? (1) Protect your mental health. Therapy can be vital as a tool for maintaining a positive healthy emotional state. (2) Protect your body by making good choices with diet and exercise. A gym membership and a few hours each week with weights and cardio add up to stress reduction and healthy weight management. (3) Finally, make new friends. On the path of a long life, old friends will fall to illness, relocation, marriage, misunderstandings, and a slew of other circumstances. Many people stop making new friends after college, even high school. One of the more significant aspects of being a survivor has been feeling the loss of friends I made in my 20s and 30s. Sadly, there’s no way to replace that history and intimacy.

Rapper Drake famously has a song called, “No New Friends.” That expression became a mantra for millennials. But as a survivor, I can tell you: they have no idea what’s ahead.